SYNOPSIS

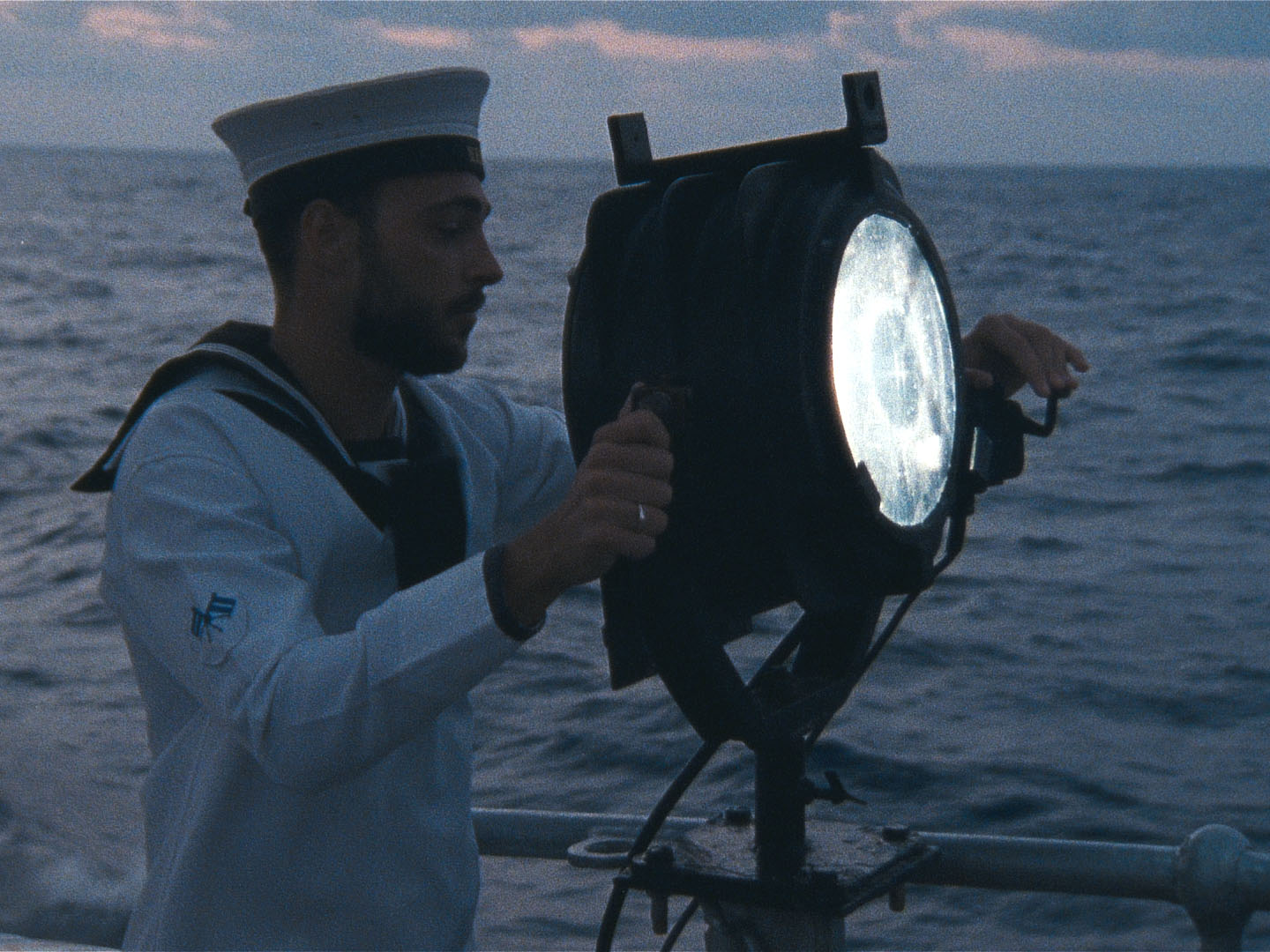

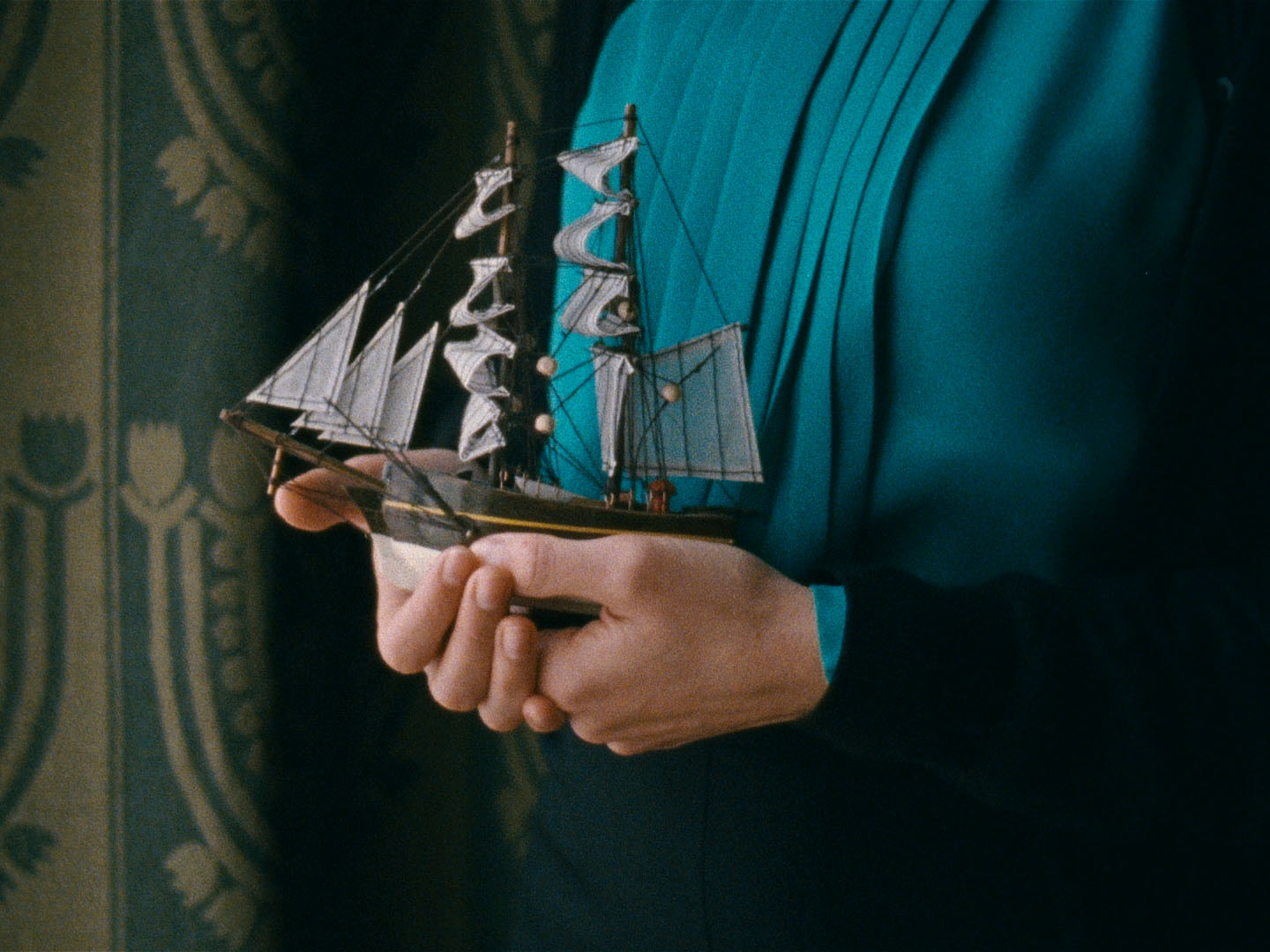

Beatriz married Henrique on the day of her 21st birthday. Henrique, a naval officer, would spend long periods at sea. Ashore, Beatriz, who learned everything from the verticality of plants, took great care of the roots of their six children. The oldest son, Jacinto (Hyacinth), my father, dreamed he could be a bird. One day, suddenly, Beatriz died. My mom didn’t die suddenly, but she too died when I was 17 years-old. On that day, me and my father met in the loss of our mothers and our relationship was no longer just that of father and daughter.

DIRECTOR’S

NOTE

For many years, I believed that my grandmother was a photograph: that picture of Beatriz, tall, vertical as a tree, with her coat over her shoulders and a smile as mysterious as Mona Lisa’s, could be found in the homes of every family member. In my father’s house, that photo was always on the cupboard where my mother’s memories and collections were kept. It was always there that my grandmother, who liked to be called Triz, lived. As if she were watching over my mother’s keepsakes.

This photograph, resembling a shrine in every home, always made me feel that there was something for me to know. I was happy for the fact that this photo could be my grandmother. At six years old, I decided that my grandmother Triz was a photograph. When I was 11, my mother fell ill. When I was 17, my mother died. I didn’t immediately realize how that brought me closer to my father. When my mother died, my father and I found each other in the absence of the word “mother”.

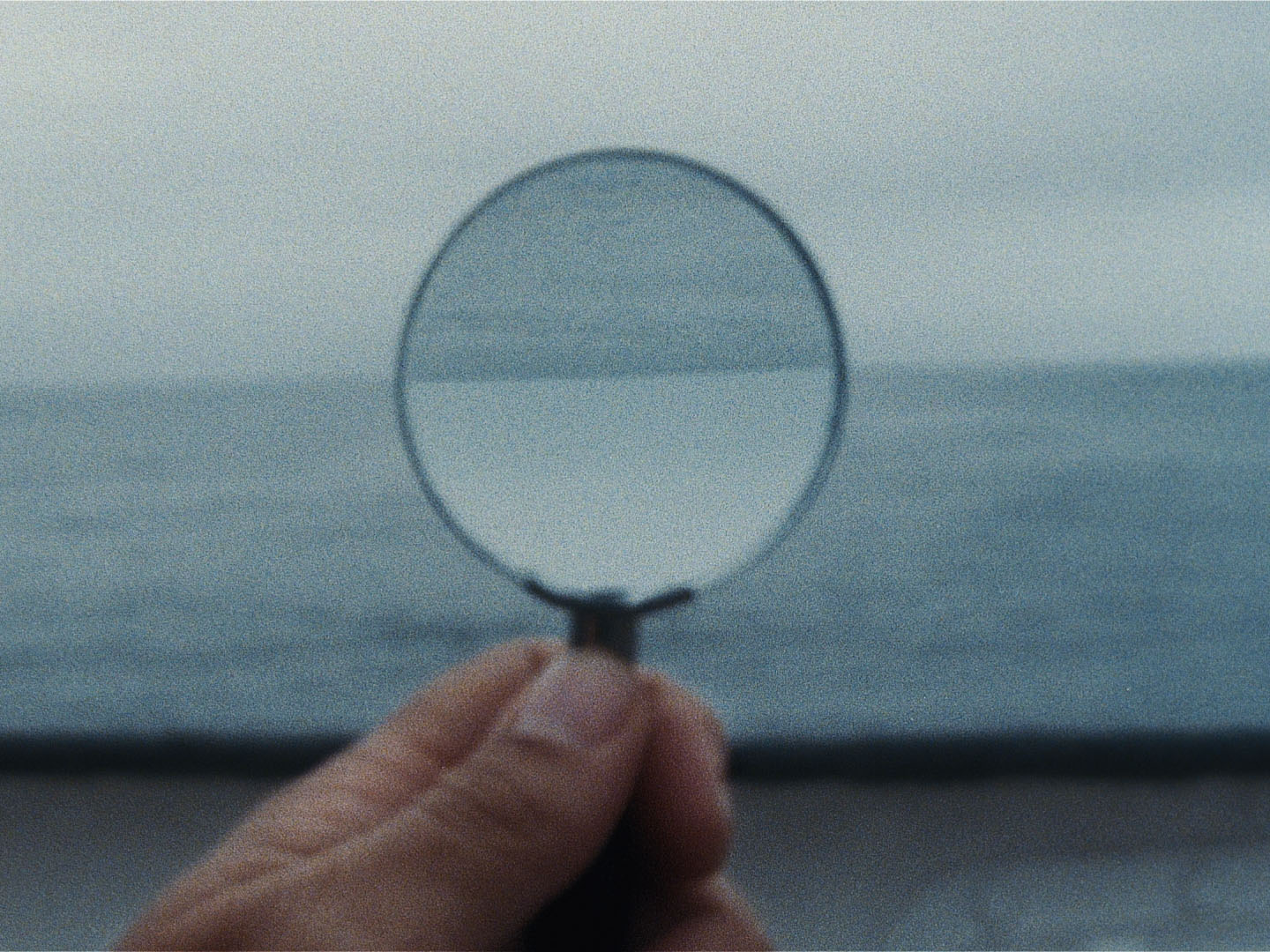

A few years passed. I left Portugal and went to study in England. I arrived in London during an economic crisis in Portugal that coincided with a personal one. One day, over Skype, my father told me that my grandfather Henrique wanted to burn the correspondence between Beatriz and him. I was extremely shocked. My father listened to my arguments, all highly emotional, and ended the conversation with: “Yes, Catarina, but these are their personal letters. It’s their intimacy and that’s no one’s business.” My father didn’t give me any hope that I might have access to the letters. At the same time, he gave me all that I needed to convince me that I wanted to make a film about Beatriz. Because it isn’t fair for dead people to die twice. This was 2014.

When the process of selling my grandparents’ house was initiated, I knew that the letters would soon be destroyed. That made me deeply sad, since I believed that Triz lived in those words. I went down to the house’s basement, where the trunks containing my grandparents’ correspondence lay under a patina of dust. Aware that I was committing an offense, I opened one of the trunks and saw a bundle of telegrams. It wasn’t Beatriz’s handwriting, but they captured her essence in simple words: “Children OK. I pray God that everything is good. Miss you tremendously.” And I, who have never believed in God, immediately believed in Beatriz.

Grandmother Beatriz was not a photograph. She existed, and I needed to know who she was. I wanted to know everything: I read about the dictatorship, about being a woman in Portugal during that time, and about what women could and could not be. I researched the associations where my grandmother had worked, I went to Ajuda cemetery, where she is buried, I went to St. Dominic Church numerous times, I went to mass at the Jerónimos Monastery... but Beatriz didn’t live in any of those places.

Beatriz lived in my father and uncles. I began a series of talks with each one about their mother. Through them, I understood and found out things not only about grandmother Triz, but also about each one of them and about a particular time. It became obvious that this film was not just about Triz. It was about my father’s mother. My mother. Mothers’ mothers. Mothers’ mothers’ mothers. But also about a certain historical period that I had not experienced: a very different time from the present one, which we have the duty not to forget. It is a great privilege to be able to live in Freedom.

Some elements of the film have not happened exactly like that. But they could have. Different dates, characters, words; my ideas projected onto my father’s and uncles’ teenage years; my anxieties projected onto their pain. Throughout these years, between the many things that my family has told me about Triz and my mother, there are enormous gaps. Because there are many things that families don’t tell you. They are part of what I fondly call the “mystery of families”.

Families are a collection of secrets. This film could never be a documentary in the sense of a film that depicts reality: which reality? And what is reality anyway? If I couldn’t have the letters, I had to invent them. If I didn’t know my father and uncles when they were young, then I had to imagine them. As for Beatriz... she grew from what they told me, what I observed, and what I imagined she must have been like. As if it were a puzzle.

The dead don’t know that they are dead. Death is a question for the living. Maybe that is why Beatriz made a vinyl record to send to Henrique during one of his sea missions. At sea, Henrique could listen to Beatriz’s and his children’s voices, who were growing up without him being able to see them. The record survived Beatriz’s death, allowing those who stayed behind to believe that she is always nearby. This film is a home for the ghosts and their memories.

SYNOPSIS

Beatriz married Henrique on the day of her 21st birthday. Henrique, a naval officer, would spend long periods at sea. Ashore, Beatriz, who learned everything from the verticality of plants, took great care of the roots of their six children. The oldest son, Jacinto (Hyacinth), my father, dreamed he could be a bird. One day, suddenly, Beatriz died. My mom didn’t die suddenly, but she too died when I was 17 years-old. On that day, me and my father met in the loss of our mothers and our relationship was no longer just that of father and daughter.

DIRECTOR’S

NOTE

For many years, I believed that my grandmother was a photograph: that picture of Beatriz, tall, vertical as a tree, with her coat over her shoulders and a smile as mysterious as Mona Lisa’s, could be found in the homes of every family member. In my father’s house, that photo was always on the cupboard where my mother’s memories and collections were kept. It was always there that my grandmother, who liked to be called Triz, lived. As if she were watching over my mother’s keepsakes.

This photograph, resembling a shrine in every home, always made me feel that there was something for me to know. I was happy for the fact that this photo could be my grandmother. At six years old, I decided that my grandmother Triz was a photograph. When I was 11, my mother fell ill. When I was 17, my mother died. I didn’t immediately realize how that brought me closer to my father. When my mother died, my father and I found each other in the absence of the word “mother”.

A few years passed. I left Portugal and went to study in England. I arrived in London during an economic crisis in Portugal that coincided with a personal one. One day, over Skype, my father told me that my grandfather Henrique wanted to burn the correspondence between Beatriz and him. I was extremely shocked. My father listened to my arguments, all highly emotional, and ended the conversation with: “Yes, Catarina, but these are their personal letters. It’s their intimacy and that’s no one’s business.” My father didn’t give me any hope that I might have access to the letters. At the same time, he gave me all that I needed to convince me that I wanted to make a film about Beatriz. Because it isn’t fair for dead people to die twice. This was 2014.

When the process of selling my grandparents’ house was initiated, I knew that the letters would soon be destroyed. That made me deeply sad, since I believed that Triz lived in those words. I went down to the house’s basement, where the trunks containing my grandparents’ correspondence lay under a patina of dust. Aware that I was committing an offense, I opened one of the trunks and saw a bundle of telegrams. It wasn’t Beatriz’s handwriting, but they captured her essence in simple words: “Children OK. I pray God that everything is good. Miss you tremendously.” And I, who have never believed in God, immediately believed in Beatriz.

Grandmother Beatriz was not a photograph. She existed, and I needed to know who she was. I wanted to know everything: I read about the dictatorship, about being a woman in Portugal during that time, and about what women could and could not be. I researched the associations where my grandmother had worked, I went to Ajuda cemetery, where she is buried, I went to St. Dominic Church numerous times, I went to mass at the Jerónimos Monastery... but Beatriz didn’t live in any of those places.

Beatriz lived in my father and uncles. I began a series of talks with each one about their mother. Through them, I understood and found out things not only about grandmother Triz, but also about each one of them and about a particular time. It became obvious that this film was not just about Triz. It was about my father’s mother. My mother. Mothers’ mothers. Mothers’ mothers’ mothers. But also about a certain historical period that I had not experienced: a very different time from the present one, which we have the duty not to forget. It is a great privilege to be able to live in Freedom.

Some elements of the film have not happened exactly like that. But they could have. Different dates, characters, words; my ideas projected onto my father’s and uncles’ teenage years; my anxieties projected onto their pain. Throughout these years, between the many things that my family has told me about Triz and my mother, there are enormous gaps. Because there are many things that families don’t tell you. They are part of what I fondly call the “mystery of families”.

Families are a collection of secrets. This film could never be a documentary in the sense of a film that depicts reality: which reality? And what is reality anyway? If I couldn’t have the letters, I had to invent them. If I didn’t know my father and uncles when they were young, then I had to imagine them. As for Beatriz... she grew from what they told me, what I observed, and what I imagined she must have been like. As if it were a puzzle.

The dead don’t know that they are dead. Death is a question for the living. Maybe that is why Beatriz made a vinyl record to send to Henrique during one of his sea missions. At sea, Henrique could listen to Beatriz’s and his children’s voices, who were growing up without him being able to see them. The record survived Beatriz’s death, allowing those who stayed behind to believe that she is always nearby. This film is a home for the ghosts and their memories.