SINOPSE

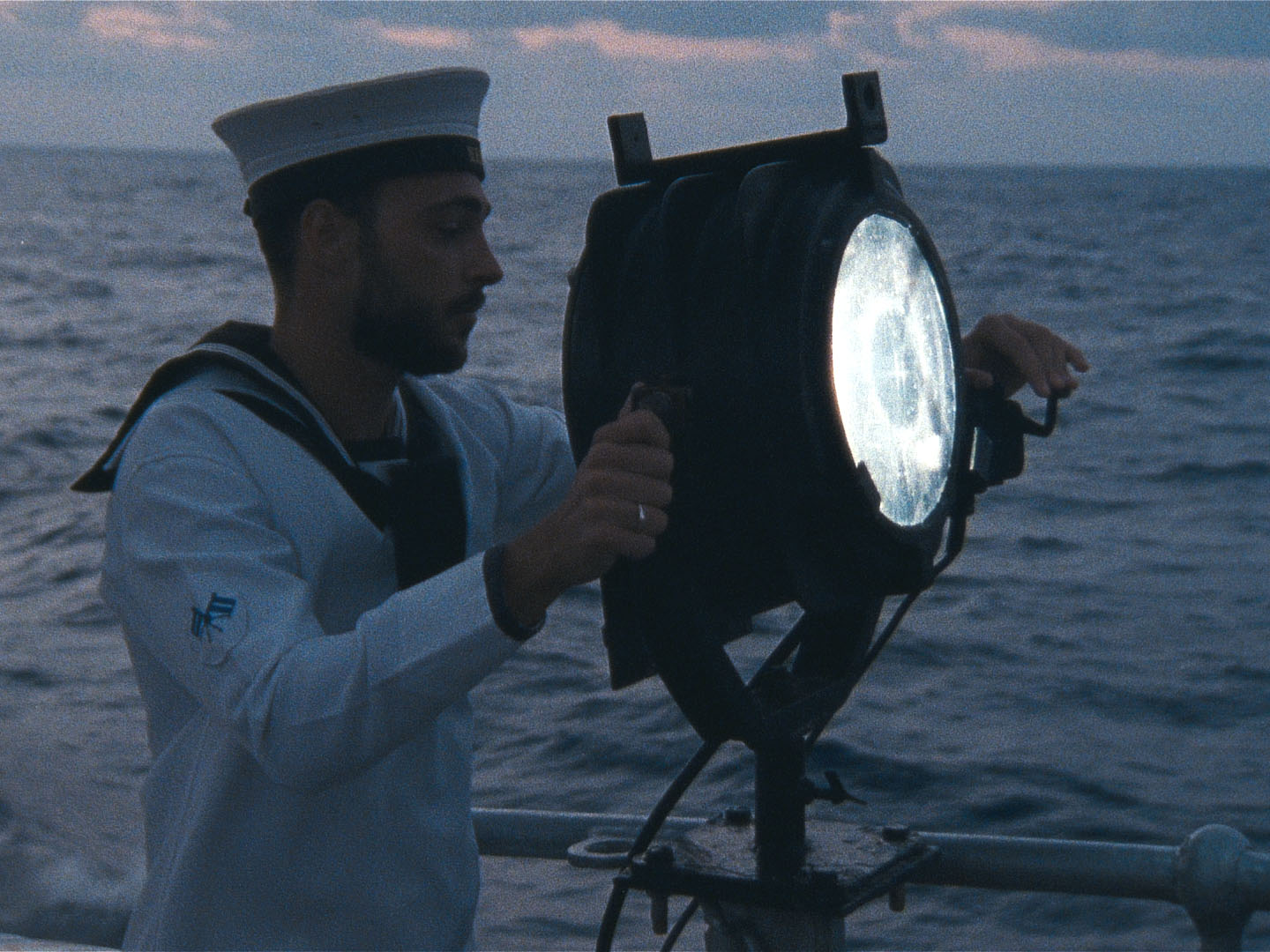

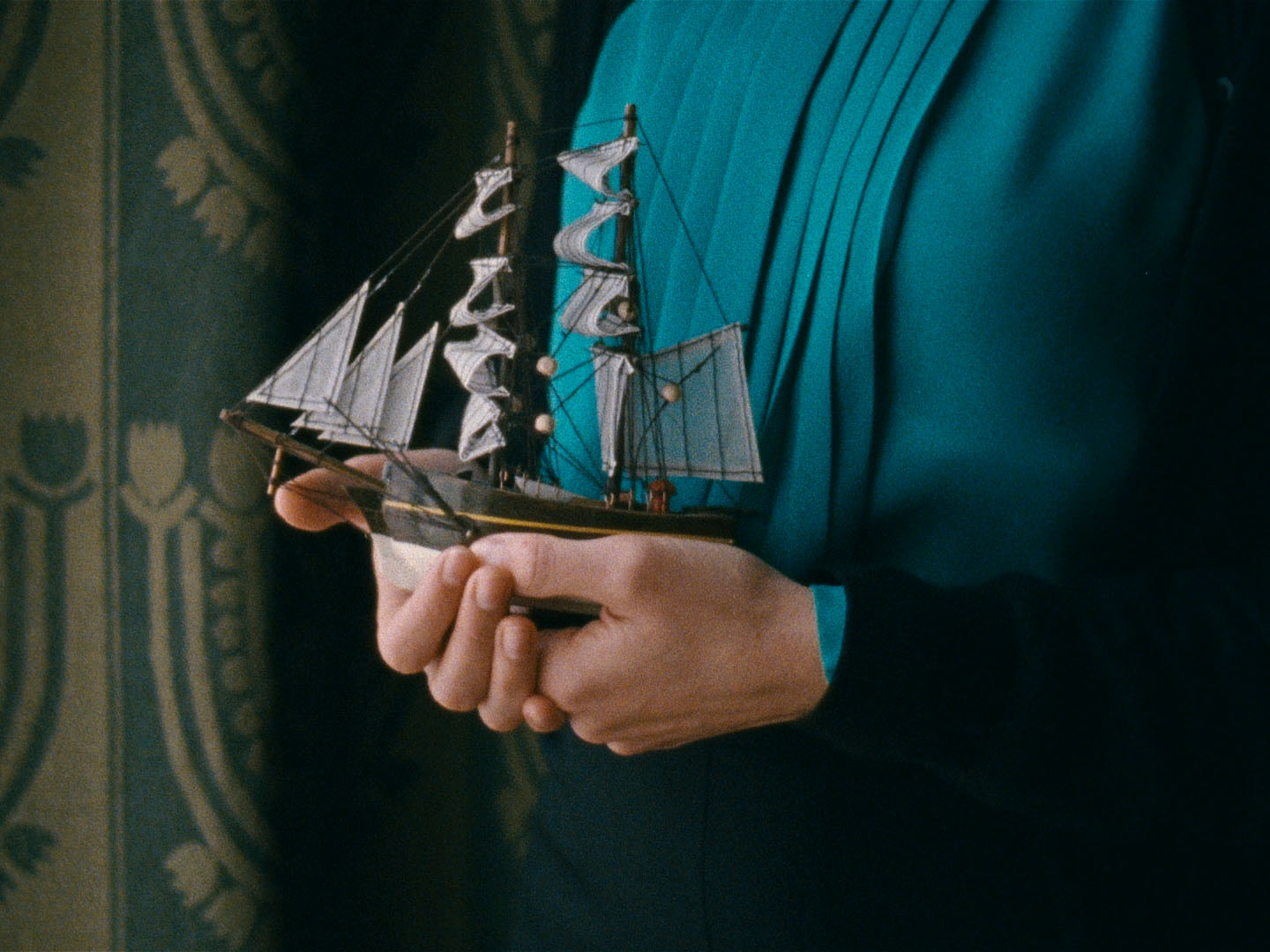

Beatriz married Henrique on the day of her 21st birthday. Henrique, a naval officer, would spend long periods at sea. Ashore, Beatriz, who learned everything from the verticality of plants, took great care of the roots of their six children. The oldest son, Jacinto (Hyacinth), my father, dreamed he could be a bird. One day, suddenly, Beatriz died. My mom didn’t die suddenly, but she too died when I was 17 years-old. On that day, me and my father met in the loss of our mothers and our relationship was no longer just that of father and daughter.

Beatriz e Henrique casaram no dia em que ela fez 21 anos. Henrique, oficial de marinha, passava largas temporadas no mar. Em terra, Beatriz, que aprendeu tudo com a verticalidade das plantas, cuidou das raízes dos 6 filhos. O filho mais velho, Jacinto, é meu pai e sonhava poder um dia ser pássaro. Um dia, subitamente, Beatriz morre. A minha mãe não morreu subitamente, mas morreu quando eu tinha 17 anos. Nesse dia, eu e o meu pai encontramo-nos na perda da mãe e a nossa relação deixou de ser só a de pai e filha.

NOTA DE

INTENÇÃO

For many years, I believed that my grandmother was a photograph: that picture of Beatriz, tall, vertical as a tree, with her coat over her shoulders and a smile as mysterious as Mona Lisa’s, could be found in the homes of every family member. In my father’s house, that photo was always on the cupboard where my mother’s memories and collections were kept. It was always there that my grandmother, who liked to be called Triz, lived. As if she were watching over my mother’s keepsakes.

Durante muitos anos acreditei que a minha avó era uma fotografia: aquela fotografia de Beatriz, alta, vertical como as árvores, com o casaco apoiado sobre os ombros e um sorriso enigmático como o de Mona Lisa, estava nas casas de todos os membros da minha família. Em casa do meu pai, esta fotografia esteve sempre em cima do móvel que guarda as memórias e colecções da minha mãe. Sempre foi ali que a avó, que gostava de ser tratada por Triz, viveu. Como que a olhar pelas recordações da minha mãe.

This photograph, resembling a shrine in every home, always made me feel that there was something for me to know. I was happy for the fact that this photo could be my grandmother. At six years old, I decided that my grandmother Triz was a photograph. When I was 11, my mother fell ill. When I was 17, my mother died. I didn’t immediately realize how that brought me closer to my father. When my mother died, my father and I found each other in the absence of the word “mother”.

Esta fotografia, que vivia em forma de altar em todas as casas, sempre me fez sentir que havia qualquer coisa para eu saber. Sentia-me feliz por aquela fotografia poder ser a minha avó. Aos 6 anos decidi que a minha avó Triz era uma fotografia. Aos 11 anos a minha mãe ficou doente. Aos 17 a minha mãe morreu. Não percebi imediatamente a forma como isso me ligava de forma estreita ao meu pai. Quando a minha mãe morreu, eu e o meu pai encontrámo-nos na ausência da palavra “mãe”.

A few years passed. I left Portugal and went to study in England. I arrived in London during an economic crisis in Portugal that coincided with a personal one. One day, over Skype, my father told me that my grandfather Henrique wanted to burn the correspondence between Beatriz and him. I was extremely shocked. My father listened to my arguments, all highly emotional, and ended the conversation with: “Yes, Catarina, but these are their personal letters. It’s their intimacy and that’s no one’s business.” My father didn’t give me any hope that I might have access to the letters. At the same time, he gave me all that I needed to convince me that I wanted to make a film about Beatriz. Because it isn’t fair for dead people to die twice. This was 2014.

Passaram-se alguns anos. Deixei Portugal e fui estudar para Inglaterra. Cheguei a Londres durante a crise económica portuguesa que batia na minha crise pessoal. Um dia tenho um skype com o meu pai que me conta que o meu avô Henrique deseja queimar a correspondência entre ele e Beatriz. Fiquei muito chocada. O meu pai escutou os meus argumentos, todos eles altamente emotivos, e terminou a conversa com: “Sim, Catarina, mas esta é a correspondência pessoal dos dois. É a sua intimidade e ninguém tem nada a ver com isso.” O meu pai não me deu qualquer tipo de esperança de aceder às cartas. E ao mesmo tempo, deu-me tudo o que precisava para ter a certeza de que queria fazer um filme sobre Beatriz. Porque não é justo os mortos morrerem duas vezes. Estávamos em 2014.

When the process of selling my grandparents’ house was initiated, I knew that the letters would soon be destroyed. That made me deeply sad, since I believed that Triz lived in those words. I went down to the house’s basement, where the trunks containing my grandparents’ correspondence lay under a patina of dust. Aware that I was committing an offense, I opened one of the trunks and saw a bundle of telegrams. It wasn’t Beatriz’s handwriting, but they captured her essence in simple words: “Children OK. I pray God that everything is good. Miss you tremendously.” And I, who have never believed in God, immediately believed in Beatriz.

Quando se iniciou o processo da venda da casa dos meus avós, soube que as cartas estavam próximas do seu fim. Aquilo dava-me muita tristeza porque eu acreditava que Triz vivia naquelas palavras. Fui até à cave da casa onde na sombra do pó jaziam os baús que continham a correspondência dos meus avós. Sabendo que cometia um delito, abri um dos baús e vi um molho de telegramas. Não tinham a letra de Beatriz, mas tinham, em simples palavras a sua essência: “Filhos bem. Rogo Deus que tudo esteja bem. Saudades infinitas.” E eu, que até à data nunca acreditei em Deus, acreditei logo em Beatriz.

Grandmother Beatriz was not a photograph. She existed, and I needed to know who she was. I wanted to know everything: I read about the dictatorship, about being a woman in Portugal during that time, and about what women could and could not be. I researched the associations where my grandmother had worked, I went to Ajuda cemetery, where she is buried, I went to St. Dominic Church numerous times, I went to mass at the Jerónimos Monastery... but Beatriz didn’t live in any of those places.

A avó Triz não era uma fotografia. Ela existia e eu precisava de saber quem era. Quis saber tudo: li sobre a ditadura, sobre ser-se mulher em Portugal nessa altura e sobre o que as mulheres podiam e não podiam ser. Pesquisei sobre as associações onde a minha avó trabalhou, fui ao cemitério da Ajuda onde está enterrada, fui vezes sem conta à igreja de S.Domingos, fui à missa nos Jerónimos... mas Beatriz não vivia ali.

Beatriz lived in my father and uncles. I began a series of talks with each one about their mother. Through them, I understood and found out things not only about grandmother Triz, but also about each one of them and about a particular time. It became obvious that this film was not just about Triz. It was about my father’s mother. My mother. Mothers’ mothers. Mothers’ mothers’ mothers. But also about a certain historical period that I had not experienced: a very different time from the present one, which we have the duty not to forget. It is a great privilege to be able to live in Freedom.

Beatriz vivia no meu pai e nos meus tios. Iniciei uma série de conversas com todos eles sobre a sua mãe. Com todos percebi e soube de coisas não só sobre a avó Triz como sobre cada um deles e sobre um determinado tempo. Tornava-se evidente que que este filme não era só acerca de Triz. Era sobre a mãe do meu pai. A minha mãe. As mães. As mães das mães. As mães das mães das mães. Mas também acerca de um determinado período histórico que eu não tinha vivido: um período tão distinto daquele que vivemos hoje e que temos o dever de não esquecer. É um grande privilégio viver em Liberdade.

Some elements of the film have not happened exactly like that. But they could have. Different dates, characters, words; my ideas projected onto my father’s and uncles’ teenage years; my anxieties projected onto their pain. Throughout these years, between the many things that my family has told me about Triz and my mother, there are enormous gaps. Because there are many things that families don’t tell you. They are part of what I fondly call the “mystery of families”.

Existem coisas neste filme que não aconteceram bem assim. Mas podiam ter acontecido. Há tempos trocados, personagens trocadas, palavras trocadas, ideias minhas projectadas nas adolescências do meu pai e dos meus tios e angustias minhas projectadas nas suas dores. Ao longo destes anos, entre as muitas coisas que a minha família me contou sobre Triz e sobre a minha mãe, existem enormes espaços em branco. Porque há muitas coisas que as famílias não contam. Elas fazem parte daquilo a que carinhosamente chamo “o mistério das famílias”.

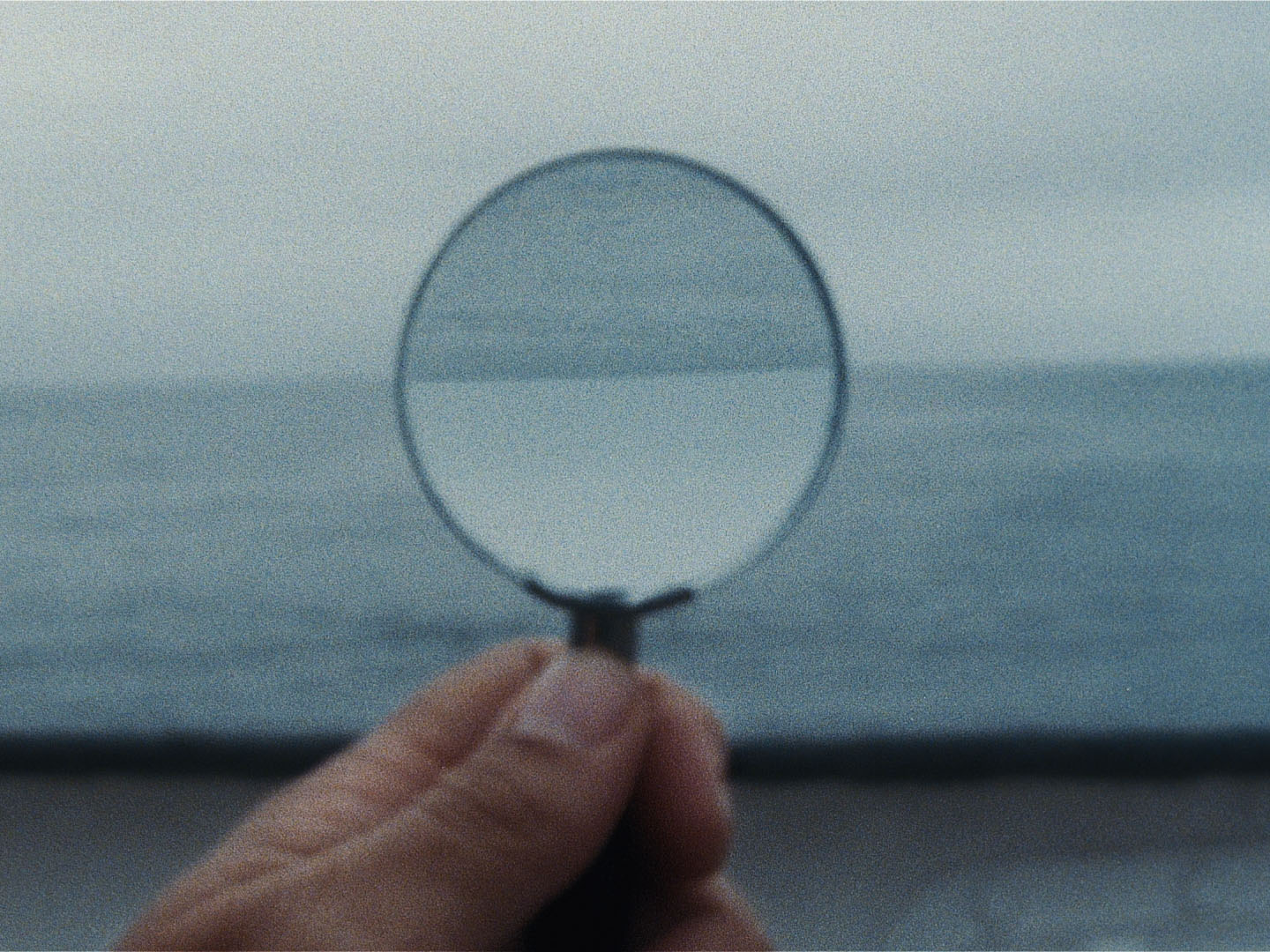

Families are a collection of secrets. This film could never be a documentary in the sense of a film that depicts reality: which reality? And what is reality anyway? If I couldn’t have the letters, I had to invent them. If I didn’t know my father and uncles when they were young, then I had to imagine them. As for Beatriz... she grew from what they told me, what I observed, and what I imagined she must have been like. As if it were a puzzle.

Families are a collection of secrets. This film could never be a documentary in the sense of a film that depicts reality: which reality? And what is reality anyway? If I couldn’t have the letters, I had to invent them. If I didn’t know my father and uncles when they were young, then I had to imagine them. As for Beatriz... she grew from what they told me, what I observed, and what I imagined she must have been like. As if it were a puzzle.

The dead don’t know that they are dead. Death is a question for the living. Maybe that is why Beatriz made a vinyl record to send to Henrique during one of his sea missions. At sea, Henrique could listen to Beatriz’s and his children’s voices, who were growing up without him being able to see them. The record survived Beatriz’s death, allowing those who stayed behind to believe that she is always nearby. This film is a home for the ghosts and their memories.

Os mortos não sabem que estão mortos. A morte é uma questão dos vivos. Talvez tenha sido por isso que Beatriz gravou um vinil que enviou para Henrique quando este estava numa das suas missões no mar. No mar, Henrique pôde ouvir a voz de Beatriz e a dos seus filhos que cresciam sem ele os poder ver. O vinil sobreviveu à morte de Beatriz, permitindo aos que ficaram acreditar que ela está sempre por perto. Este filme é uma casa para os fantasmas e para as suas memórias.

SINOPSE

Beatriz married Henrique on the day of her 21st birthday. Henrique, a naval officer, would spend long periods at sea. Ashore, Beatriz, who learned everything from the verticality of plants, took great care of the roots of their six children. The oldest son, Jacinto (Hyacinth), my father, dreamed he could be a bird. One day, suddenly, Beatriz died. My mom didn’t die suddenly, but she too died when I was 17 years-old. On that day, me and my father met in the loss of our mothers and our relationship was no longer just that of father and daughter.

Beatriz e Henrique casaram no dia em que ela fez 21 anos. Henrique, oficial de marinha, passava largas temporadas no mar. Em terra, Beatriz, que aprendeu tudo com a verticalidade das plantas, cuidou das raízes dos 6 filhos. O filho mais velho, Jacinto, é meu pai e sonhava poder um dia ser pássaro. Um dia, subitamente, Beatriz morre. A minha mãe não morreu subitamente, mas morreu quando eu tinha 17 anos. Nesse dia, eu e o meu pai encontramo-nos na perda da mãe e a nossa relação deixou de ser só a de pai e filha.

NOTA DE

INTENÇÃO

For many years, I believed that my grandmother was a photograph: that picture of Beatriz, tall, vertical as a tree, with her coat over her shoulders and a smile as mysterious as Mona Lisa’s, could be found in the homes of every family member. In my father’s house, that photo was always on the cupboard where my mother’s memories and collections were kept. It was always there that my grandmother, who liked to be called Triz, lived. As if she were watching over my mother’s keepsakes.

This photograph, resembling a shrine in every home, always made me feel that there was something for me to know. I was happy for the fact that this photo could be my grandmother. At six years old, I decided that my grandmother Triz was a photograph. When I was 11, my mother fell ill. When I was 17, my mother died. I didn’t immediately realize how that brought me closer to my father. When my mother died, my father and I found each other in the absence of the word “mother”.

A few years passed. I left Portugal and went to study in England. I arrived in London during an economic crisis in Portugal that coincided with a personal one. One day, over Skype, my father told me that my grandfather Henrique wanted to burn the correspondence between Beatriz and him. I was extremely shocked. My father listened to my arguments, all highly emotional, and ended the conversation with: “Yes, Catarina, but these are their personal letters. It’s their intimacy and that’s no one’s business.” My father didn’t give me any hope that I might have access to the letters. At the same time, he gave me all that I needed to convince me that I wanted to make a film about Beatriz. Because it isn’t fair for dead people to die twice. This was 2014.

When the process of selling my grandparents’ house was initiated, I knew that the letters would soon be destroyed. That made me deeply sad, since I believed that Triz lived in those words. I went down to the house’s basement, where the trunks containing my grandparents’ correspondence lay under a patina of dust. Aware that I was committing an offense, I opened one of the trunks and saw a bundle of telegrams. It wasn’t Beatriz’s handwriting, but they captured her essence in simple words: “Children OK. I pray God that everything is good. Miss you tremendously.” And I, who have never believed in God, immediately believed in Beatriz.

Grandmother Beatriz was not a photograph. She existed, and I needed to know who she was. I wanted to know everything: I read about the dictatorship, about being a woman in Portugal during that time, and about what women could and could not be. I researched the associations where my grandmother had worked, I went to Ajuda cemetery, where she is buried, I went to St. Dominic Church numerous times, I went to mass at the Jerónimos Monastery... but Beatriz didn’t live in any of those places.

Beatriz lived in my father and uncles. I began a series of talks with each one about their mother. Through them, I understood and found out things not only about grandmother Triz, but also about each one of them and about a particular time. It became obvious that this film was not just about Triz. It was about my father’s mother. My mother. Mothers’ mothers. Mothers’ mothers’ mothers. But also about a certain historical period that I had not experienced: a very different time from the present one, which we have the duty not to forget. It is a great privilege to be able to live in Freedom.

Some elements of the film have not happened exactly like that. But they could have. Different dates, characters, words; my ideas projected onto my father’s and uncles’ teenage years; my anxieties projected onto their pain. Throughout these years, between the many things that my family has told me about Triz and my mother, there are enormous gaps. Because there are many things that families don’t tell you. They are part of what I fondly call the “mystery of families”.

Families are a collection of secrets. This film could never be a documentary in the sense of a film that depicts reality: which reality? And what is reality anyway? If I couldn’t have the letters, I had to invent them. If I didn’t know my father and uncles when they were young, then I had to imagine them. As for Beatriz... she grew from what they told me, what I observed, and what I imagined she must have been like. As if it were a puzzle.

The dead don’t know that they are dead. Death is a question for the living. Maybe that is why Beatriz made a vinyl record to send to Henrique during one of his sea missions. At sea, Henrique could listen to Beatriz’s and his children’s voices, who were growing up without him being able to see them. The record survived Beatriz’s death, allowing those who stayed behind to believe that she is always nearby. This film is a home for the ghosts and their memories.

Durante muitos anos acreditei que a minha avó era uma fotografia: aquela fotografia de Beatriz, alta, vertical como as árvores, com o casaco apoiado sobre os ombros e um sorriso enigmático como o de Mona Lisa, estava nas casas de todos os membros da minha família. Em casa do meu pai, esta fotografia esteve sempre em cima do móvel que guarda as memórias e colecções da minha mãe. Sempre foi ali que a avó, que gostava de ser tratada por Triz, viveu. Como que a olhar pelas recordações da minha mãe.

Esta fotografia, que vivia em forma de altar em todas as casas, sempre me fez sentir que havia qualquer coisa para eu saber. Sentia-me feliz por aquela fotografia poder ser a minha avó. Aos 6 anos decidi que a minha avó Triz era uma fotografia. Aos 11 anos a minha mãe ficou doente. Aos 17 a minha mãe morreu. Não percebi imediatamente a forma como isso me ligava de forma estreita ao meu pai. Quando a minha mãe morreu, eu e o meu pai encontrámo-nos na ausência da palavra “mãe”.

Passaram-se alguns anos. Deixei Portugal e fui estudar para Inglaterra. Cheguei a Londres durante a crise económica portuguesa que batia na minha crise pessoal. Um dia tenho um skype com o meu pai que me conta que o meu avô Henrique deseja queimar a correspondência entre ele e Beatriz. Fiquei muito chocada. O meu pai escutou os meus argumentos, todos eles altamente emotivos, e terminou a conversa com: “Sim, Catarina, mas esta é a correspondência pessoal dos dois. É a sua intimidade e ninguém tem nada a ver com isso.” O meu pai não me deu qualquer tipo de esperança de aceder às cartas. E ao mesmo tempo, deu-me tudo o que precisava para ter a certeza de que queria fazer um filme sobre Beatriz. Porque não é justo os mortos morrerem duas vezes. Estávamos em 2014.

Quando se iniciou o processo da venda da casa dos meus avós, soube que as cartas estavam próximas do seu fim. Aquilo dava-me muita tristeza porque eu acreditava que Triz vivia naquelas palavras. Fui até à cave da casa onde na sombra do pó jaziam os baús que continham a correspondência dos meus avós. Sabendo que cometia um delito, abri um dos baús e vi um molho de telegramas. Não tinham a letra de Beatriz, mas tinham, em simples palavras a sua essência: “Filhos bem. Rogo Deus que tudo esteja bem. Saudades infinitas.” E eu, que até à data nunca acreditei em Deus, acreditei logo em Beatriz.

A avó Triz não era uma fotografia. Ela existia e eu precisava de saber quem era. Quis saber tudo: li sobre a ditadura, sobre ser-se mulher em Portugal nessa altura e sobre o que as mulheres podiam e não podiam ser. Pesquisei sobre as associações onde a minha avó trabalhou, fui ao cemitério da Ajuda onde está enterrada, fui vezes sem conta à igreja de S.Domingos, fui à missa nos Jerónimos... mas Beatriz não vivia ali.

Beatriz vivia no meu pai e nos meus tios. Iniciei uma série de conversas com todos eles sobre a sua mãe. Com todos percebi e soube de coisas não só sobre a avó Triz como sobre cada um deles e sobre um determinado tempo. Tornava-se evidente que que este filme não era só acerca de Triz. Era sobre a mãe do meu pai. A minha mãe. As mães. As mães das mães. As mães das mães das mães. Mas também acerca de um determinado período histórico que eu não tinha vivido: um período tão distinto daquele que vivemos hoje e que temos o dever de não esquecer. É um grande privilégio viver em Liberdade.

Existem coisas neste filme que não aconteceram bem assim. Mas podiam ter acontecido. Há tempos trocados, personagens trocadas, palavras trocadas, ideias minhas projectadas nas adolescências do meu pai e dos meus tios e angustias minhas projectadas nas suas dores. Ao longo destes anos, entre as muitas coisas que a minha família me contou sobre Triz e sobre a minha mãe, existem enormes espaços em branco. Porque há muitas coisas que as famílias não contam. Elas fazem parte daquilo a que carinhosamente chamo “o mistério das famílias”.

As famílias são uma colecção de segredos. Este filme nunca poderia ser um documentário no sentido de um filme que retrata “a” realidade: qual das realidades? E, afinal de contas, o que é isso da realidade? Se eu não podia ter as cartas, tinha de as inventar. Se não conheci o meu pai e os meus tios enquanto eram jovens, então tinha de os imaginar. E em relação a Beatriz... ela foi crescendo com o que me contaram, com o que eu observei e com aquilo que imaginei que ela seria. Como um puzzle.

Os mortos não sabem que estão mortos. A morte é uma questão dos vivos. Talvez tenha sido por isso que Beatriz gravou um vinil que enviou para Henrique quando este estava numa das suas missões no mar. No mar, Henrique pôde ouvir a voz de Beatriz e a dos seus filhos que cresciam sem ele os poder ver. O vinil sobreviveu à morte de Beatriz, permitindo aos que ficaram acreditar que ela está sempre por perto. Este filme é uma casa para os fantasmas e para as suas memórias.